Certain moments in our lives end up becoming pivotal points of no return: decisive events after which we are never the same, moments that define and shape us so substantially that we can’t ignore them despite our strongest attempts to do so. For me, one such occasion occurred on the morning of May 18, 2018, when I took a deep, shaky breath and stepped into an elevator that crawled to the top floor of NewYork-Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center.

At that point in my life, I remember feeling unsettlingly vulnerable, like I had absolutely no idea where I was headed or what was going to happen next. In terms of my professional life, I was finishing up the first year of my PhD at the very institution where I was now seeking emergency medical care. Sure, I was in a program with regulations and guidelines that told me where I was headed next, but I was still in the midst of lab rotations—which involved trying to impress a lot of different people and doing a lot of things I wasn’t very good at—and I had no idea what my research would focus on over the next four to five years. In terms of my personal life, I was in complete shambles. A few months prior, I had gone through a pretty rough breakup from the person I had been dating for almost two years. My self-confidence was at an all-time low, and I was engaging in a lot of risky behavior with people I barely even knew, which is sort of the reason I had ended up here, on the top floor of the hospital.

The HIV clinic and treatment center at Weill Cornell, officially known as the Center for Special Studies (CSS), is on the 24th floor of a sprawling building on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, nestled into a corner at the nexus of the Rockefeller University’s leafy campus and the steadily flowing East River. The views of several New York landmarks like the Queensboro Bridge, the Empire State Building, and the UN from that height are stunning. I distinctly remember taking a photo and posting it to Instagram with some Frank Sinatra lyrics about making it here and making it anywhere, pretending that I wasn’t afraid of what had transpired over the past 12 hours and the effect it might have on my life, hiding that I felt like simultaneously sobbing and throwing up and sleeping for hours and hours and hours.

Sixty minutes prior, I had fought back tears as I exited the lobby of a luxurious Midtown high-rise in which every single unit was way out of my price range. I speed-walked down West 42nd Street, awash with the golden warmth of the rising sun but feeling ice-cold on the inside. The night before, I had let a fear of awkwardness, of disappointing someone, of not being the type of young gay man that I felt I was expected to be, persuade me to do something that endangered my health, and now I had potentially exposed myself to HIV. Well aware of this fact, I hastily Googled “how to get PEP in NYC” as I descended the stairs into the subway and decided what to do next.

HIV, which stands for human immunodeficiency virus, was discovered as the cause of AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) in 1983. During that decade and the one that followed, the AIDS crisis ravaged the LGBTQ+ communities of the United States, particularly affecting men and trans women of color due to a lethal combination of a lack of knowledge about the virus and its transmission, stigmatization of the people affected, and refusal of governmental agencies to allocate resources to fighting the disease. In those days, a positive diagnosis of HIV was terminal and meant that your days were numbered.

Thankfully, due to the dedication and persistence of doctors, nurses, activists, community organizers, and researchers, treatments now exist that can boost immunity and keep the virus at bay, preventing HIV infection from progressing to AIDS. Some of these treatments work so well that they reduce the amount of the virus in patients’ blood to levels that are undetectable in lab tests, meaning that, with proper maintenance of treatment, these people cannot pass on the virus to their sexual partners. Over the course of thirty years, infection with HIV has been transformed from a death sentence into a manageable, chronic condition not unlike asthma or diabetes.

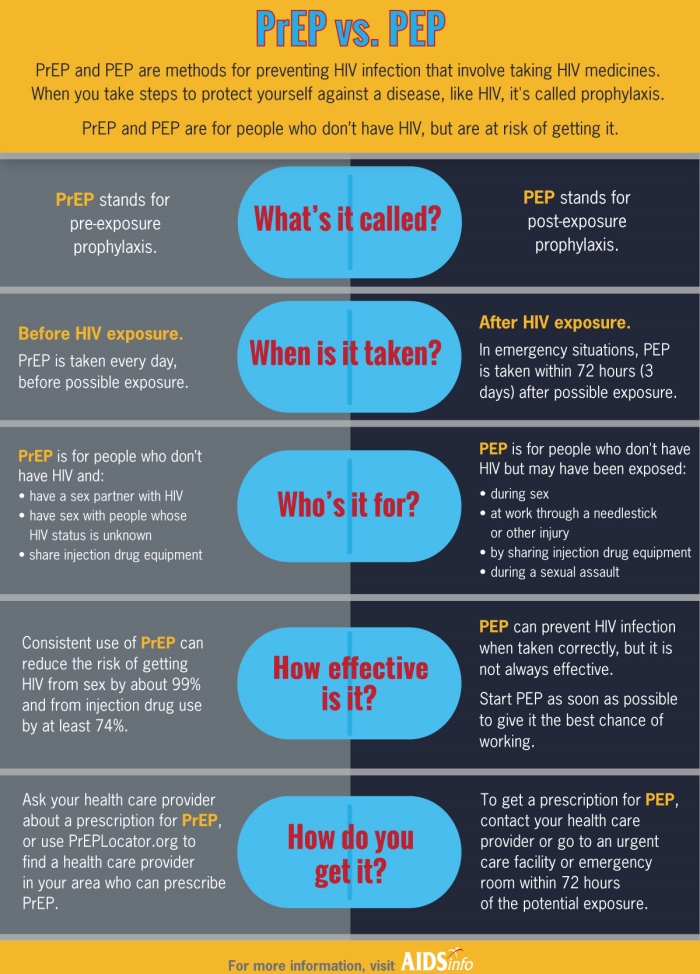

These practically magical medications, broadly known as antiretroviral therapies (ART), target a variety of processes that allow HIV to replicate within the body. In addition to treating people who are already living with HIV, some of these medications can also be used to prevent viral transmission to people who are not yet infected. There are two arms to this preventative approach: PrEP, which stands for pre-exposure prophylaxis, and PEP, which stands for post-exposure prophylaxis.

(Prophylaxis is a fancy medical term for a medication that is taken to prevent, rather than treat, a disease.)

Source: National Institutes of Health

PrEP, which has been approved in the United States since 2012, is a medication taken daily that aims to prevent HIV transmission before an exposure has occurred. Truvada, the brand name of this medication, is a single-pill combination of two molecules—emtricitabine and tenofovir—that combat HIV in different ways. The concept of PrEP is that taking these medicines daily keeps a constant level of HIV-fighting drugs in your body. This way, if and when you are exposed to the virus, the drugs can begin working instantaneously and prevent HIV infection from taking hold. When taken as directed, PrEP has been shown to be more than 99% effective at preventing HIV transmission. Isn’t that incredible? Unfortunately, the patent on Truvada has caused it to become prohibitively expensive for people who need it the most, and a lack of access to reliable medical care has prevented PrEP from reaching its fullest potential worldwide. (Maybe I can talk more about this in a future post?)

In contrast to PrEP, PEP is given after a potential exposure has occurred. The goal of this treatment is still to prevent HIV infection, but because the virus is potentially already in the patient’s bloodstream, the approach has to be a bit more aggressive in order to increase the chances of stopping the virus in its tracks. PEP usually involves three medications in total: Truvada, as mentioned before, in combination with a third drug that targets a different part of the viral replication cycle. PEP is most effective when it is started within 24 hours of a potential exposure to HIV, and it is usually taken for 30 days.

I consider myself lucky because my graduate school training had given me all of the information about HIV, PrEP, and PEP that I laid out above. I am also very fortunate to (1) have good health insurance through my program and (2) reside in New York City, where the department of health has instituted a program that provides access to PrEP and PEP for people who need it, regardless of insurance coverage or ability to pay. Many people do not have such privileges.

“Do you have an appointment with us?” the CSS receptionist asked politely as I approached the desk after snapping a photo of the view.

“Um, no,” I stammered, unsure of how to go about this. “I’m here because I need more information about getting PEP.”

She stopped typing and looked at me. “Were you exposed?”

“Potentially,” I answered. The look of concern in her eyes was almost alarming but mostly comforting. It felt good to know that somebody cared. It wasn’t just my burden anymore. The secret was out.

“Wait here,” she said, gesturing to an array of chairs. “I’ll have a doctor meet with you as soon as they can.”

She kept her promise. Despite not having an appointment and being busy with many other patients, a clinician whom I will call Dr. E made time to see me. And this appointment, with this doctor, on this day, changed the course of my life forever. After a thorough questioning of my reason for coming to the clinic and listening to me explain what had happened, my newest doctor and I agreed that I should initiate PEP as soon as possible. I tried my hardest to remain emotionless and calm, but once she began explaining the medications I would be taking and what to expect from the process going forward, I couldn’t hold back the tears anymore.

When this happened, Dr. E stopped talking and took my hand. “What’s going through your head right now?” she softly asked.

“I already know all of this,” I muttered. “I know how PEP works. I’m a pharmacology student here. I’m just upset because this was all so preventable. I knew better but I took the risk anyway and I’m mad at myself for it.”

Dr. E looked me in the eyes and said, “People make mistakes all the time. We’re human. You can’t change what happened. But what you can do is take control of your health and make different decisions in the future. That’s why you’re here. It’s not too late, and you did the right thing. And even if this treatment doesn’t work out exactly how we’d like it to, the CSS team will be here for you.” And in that moment, the tears stopped flowing. She was right, and she had said exactly what I needed to hear.

Before I walked into the hospital that day, I felt ashamed, afraid, and alone because of the choices I had made and the position I had put myself in. After my appointment with Dr. E, I left feeling informed, supported, valued, and empowered to make good decisions about my health and wellness. Dr. E toed the fine line that all physicians must—educating their patients about the particulars of science, health, and medicine, but also connecting with those people on a personal level and acknowledging their humanity. During that appointment on May 18, I, a gay pharmacology graduate student, didn’t need to hear about how antiretrovirals worked, but what I did need to hear was that people make mistakes, that somebody cared about what I was going through, and that, no matter what happened, everything was going to turn out alright.

I strolled out of NewYork-Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center that day with PEP in my hand and, oddly enough, a pep in my step. (Sorry, not sorry for the pun.) The sunlight still felt warm, and my insides didn’t feel as cold as they had before. I couldn’t stop thinking about Dr. E and how she had so masterfully recognized my needs and acknowledged them during our appointment. I thought about how maybe I could do that for people. The sinking feeling that had taken up residence in my stomach that morning melted away and transformed into butterflies. Could I be that person for patients? Was I wrong about research, and was medicine actually my calling?

Since that day, I have harbored a fervent passion to make a difference for patients in the way that my care team at the CSS did for me. This transformational experience has led me to the conclusion, after years of studying biomedical sciences and pursuing a career in academic science, that I don’t have to choose one path or the other. I can have a profession that combines my desire for learning and discovery with a passion for connecting with and serving people in need.

My current goals include attending medical school after I finish my PhD, completing a residency in internal medicine, and pursuing a fellowship in infectious diseases (ID), eventually working my way up to a position where I can both conduct research and care for patients. I am especially passionate about specializing in ID because it encompasses not only my research interest in tuberculosis, which predominantly affects low-income and poverty-stricken communities worldwide, but also HIV/AIDS, which has affected my personal life and the lives of countless other LGBTQ+ folks. I also intend to work to increase healthcare access and reduce disparities in care for marginalized communities, knowing full well that my privileged position in society contributed greatly to receiving the medical care that I have described in this post.

I often wonder what would’ve happened if I didn’t go to see Dr. E that day. Perhaps I would have stumbled upon my passion for patient care and medicine through a different route. Regardless, I did make that trip to the top floor of NewYork-Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center, and in that place, on that day, Dr. E gave me more than a course of medication to help prevent a viral infection. She gave me something more important than routine medical advice. She gave me hope. She gave me tools for future success and a sense of agency about my own health. And finally, she helped me to see that what I really want to do with my talents is to help other members of my community live full and healthy lives, the way she did for me.

I can’t think of a better vocation for myself than that.

An image of the card I wrote to Dr. E, in which I thanked her for her help and expressed how my visit with her changed my career trajectory for the better.

For more information and resources about HIV/AIDS, including PrEP, PEP, and ART, please visit https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/index.html.

Great article Kyle! Anytime you come home I’d love for you to speak to my anatomy and physiology students! Much love!

LikeLike